|

Since the release of Deep Tasting Chocolate & Whiskey, in November, I've been interiewed for podcasts by Lauren Heineck of WKND Chocolate (wkndchocolate.com, podcast #18) and Mark Gillespie of Whiskycast.com (episode #680, February 11) for Valentine's Day. Canadian whisky expert, Davin de Kergommeaux, author of Canadian Whisky: the New Portable Expert, graciously mentioned my book in an op ed for Whisky Magazine, #149. A review of my book appeared on the website Bourbon & Banter (bourbonbanter.com) and journalist Simran Sethi quoted me in an article about whisky and chocolate. Whisky Magazine invited me to write an article on pairing chocolate with whisky in which I’ve issued a challenge to pair it with other foods too. I’ve begun a data base to record and analyze those parings. The Whisky Magazine article should be out in mid April. I'll be breaking more news as it happens. Check back.

0 Comments

When it comes to whiskey, it is said that anywhere from 60-80% of the flavor comes from the wood in which it is aged.

What about chocolate? Cacao beans spend approximately a week or less fermenting in wood. Like whiskey, ethanol and many other compounds are produced. With respect to whiskey, oxygenation occurs. The wood breathes, in, out, and with it, the young whiskey is absorbed and released with tannins and compounds, such as vanillin, picked up from the wood. The whiskey may also breathe in other environmental aromas, such as salt air. Whiskey spends a long time in wood—years. Chocolate does not. So, does the wood matter? The best wood for initial aging of whiskey is oak, with American white oak popularly used due to the tightness of the grain which prevent leaks and the lovely flavor notes it imparts to the whiskey. ‘But in what kind of wood do we ferment cacao? From the responses given to my first inquiries, it seems to vary from region to region. If the wood interacts in such a way as to influence the flavor of the cacao, it would be helpful to describe the nature of the aroma compounds that are produced and to quantify the degree that it occurs. Researchers, please step forward! Post Script: Remember To'ak from my last blog?Turns out they've been doing interesting experiments and are producing chocolate nibs aged in various whisky, cognac and other casks. Now they've got my attention!  How much would you pay for a chocolate bar or a bottle of whiskey? $260.-315.US for 1.5 ounces of chocolate? From $400. to $5000. per bottle of whiskey? What is going on here?And more importantly, should you consider shelling out for these products? The price-tag of To'ak Chocolate was scandalous enough in 2014 to launch a successful publicity campaign and a flurry of debate within chocolate circles. I looked at the website–very nice– their packaging (see photo)–wood tongs and box made of the same Spanish Elm used during fermentation--okay, conveys a certain attention to detail, still, it screamed HYPE to me. Produced in Ecuador, the company called the beans "Nacional," but the genetics actually revealed a hybrid. No surprise to anyone who knows the history of Arriba cacao in Ecuador The C-spot rated the To'ak an 8.51 (on a scale of 1-10) and awarded the cumulative with only 3-1/2 stars. Personally, I thought the C-spot had been extremely kind when later I had been able to taste a sample of the 81% for free as a staff reviewer. When I heard To'ak had been awarded heirloom status, I wondered whether someone had been paid-off. But I've been assured there had been no corruption involved. Apparently, with expert handling and a significant amount of sugar (down to 68% cacao), the Heritage Cacao Preservation Initiative produced samples that were indeed worth premium prices. But what is the value of a premium-priced bar? The very best, small batch (1000 bars?) artisan chocolate is priced under $25 for approximately 1.5- 2.5 ounces. In fact, artisan bars vary widely from about $8.99 to $15 for most that are domestically produced. Now, to be fair, To'ak's batch size was only a few hundred bars. Anything produced on so small a scale as to be considered rare, certainly, merits higher prices. But there's a difference between what a producer must charge to make their efforts financially worthwhile and what is realistic to expect consumers to bear. Throw in the fancy-shmancy wood box and tongs, okay--still, come on... Here's the question that gets to the heart of the matter: Take me, a total chocolate fanatic, who easily plunks down top dollar for quality chocolate, and has to try every bar out there, would I ever pay for a bar of To'ak? No, I would not. That brings us to the runaway train of inflation in the American whiskey market. To be fair, it's not just American spirits; world whiskies, particularly Scotch and Japanese, have risen astronomically too. But how do you separate value from hype? Well, you have to educate your palate and learn to trust your instincts. Recently, I've been working on my next book which, I hope, will enable you to do just that, and more. It's about pairing chocolate and spirits. Pairing has become a big area of interest in the last few years–pairing with wine, with beer, with cheese, with your Uncle Tony... I'm not big on pairing, preferring to focus on one single piece of dark chocolate at a time, and savoring mindfully. Really, isn't a great piece of chocolate enough! If you're really, really tasting it? And personally, I approach whisky the same way–straight, or "neat." I'm just not a cocktail kinda gal. Though cocktails maybe fashionable again, I'm not. But since people are doing this pairing thing, I felt, strictly speaking as a flavor maven, a certain responsibility to help people who are intrigued with pairing, to do it in a way that makes sense and will empower them with the tools to make good choices on their own. Most books, whether on spirits or chocolate, simply throw out a few examples of pairings, then turn you loose on the local merchants. My forthcoming book, working title–The Deep Tasting Guide™To Pairing Chocolate and Whiskey–will present a system for optimal pairing. Hopefully, just as was the goal of my first book, after reading my next, you will be able to trust your own senses and not be bamboozled. In the process of researching the pairing book, I've had to taste a lot of whisky/whiskey. Think crash course: readings, tastings, purchasing, sweeping drams ordered in bars into my hip flask and stealing off into the night, almost every night. Because if you're going to pair anything, you need to thoroughly know both components. This is the problem with a lot of wine and spirits books already on the bookshelves: They really don't know their chocolate! I was just discussing this just the other day with the delightful chocolate and wine sommelier, Roxanne Browning. So, yes, I've had to taste a lot of whisky--Scotch, Japanese, Taiwanese, Canadian, French, and whiskey–American bourbon, rye, wheat whiskey, and so on. Now, I must stress the word "taste" rather than drink. I'm not really a drinker. Truly, I'm not. In fact, I'm sober to such an excessive degree that my resolution for Lent is to give up sobriety. And I'm not doing so well. When working with spirits in my kitchen lab, I usually ingest less than an ounce, probably less than a half ounce. It's a prolonged and repetitive "nosing," then a sip or two. If I'm attending a tasting, I generally don't swallow more than a sip or two there either, and generally only if the whisky is exceptional. I confess to spitting.(They're getting used to me.) But though it may come as a shock to liquor store customers, that's what the master distillers do, so... I don't like feeling even mildly buzzed. I meditate or exercise when stressed. If you're drinking or eating chocolate to solve stress issues or to anesthetize, let's face it–that's self-medicating. My experience of chocolate, and now spirits, is about actively engaging the senses and savoring. It's about feeling more, not less. So my approach to combining chocolate and spirits is about fully experiencing both, individually and together. A successful match for me is not a matter of simple compatibility, but that something additional, hopefully better, emerges in the form of enhanced or wholly additional flavor notes. Whiskey hype, American style. Researching whiskey required me to risk a bunch of dollars to gain perspective. So, some time ago, I attended a tasting of rare American whiskey (see photo below). I needed to understand why the Pappy Van Winkle bourbons and Van Winkle Family Reserve Rye were all the rage and selling at such high prices. Why did they cost even more than top of the line, and in some cases 2-3 times more, than relatively rare, superbly crafted Scotch? And now, why were the Van Winkle prices pushing up to cost of other whiskeys in the Buffalo Trace line, particularly the Weller line, said to resemble the Van Winkles in every way but age and space they occupy in the warehouse. While these price surges haven't reached every American whiskey out there, the Van Winkle phenomena has been making an inflationary impact for vast numbers of American whiskeys. The other pressure on price is due to the craft whiskey movement--the topic of a future blog post. To a large degree, rarity is the operative word with respect to Van Winkle. Whenever you age whiskey or whisky, it means setting the barrels aside and using space for many years. How much of a warehouse can you afford to occupy? Because you need to move merchandise to make any money, aging means deferred profits. Therefore, the distilleries may only put aside a limited number of barrels for long aging (18 or more years). And make no mistake, the supply of Van Winkles is shrinking. But even the Weller line is experiencing a scarcity, whether real or manufactured. But we would hope that price also reflects quality, not just scarcity, and that aging adds up to a better tasting, richer whiskey. Here's the thing, though, if you're aging in a single barrel, there comes a time when you max out the flavor from the wood. This is why after a certain number of years, the master distillers or malt masters in Scotland, particularly in recent history, do sequential maturing, first for a number of years in oak or ex-American bourbon casks, then another number of years in an ex-sherry casks, then sometimes finishing in still other cask that may have contained port or wines. There may be any number of casks used and any combination, as long as it suits the master distiller. The aging process is a huge part of a malt master's art and the pay off is exquisitely, flavor-orchestrated whiskies. If you were to taste a 12 year old Dalmore or Macallan, then taste one in excess of 20 years, you would see immediately what I mean by increasing complexity. Until recently, that kind of finishing or complexity in aging wasn't really part of American whiskey production.That is changing, however. For me the 23 year old Pappy Van Winkle is not richer, but thinner, more straight oak than the 12 year or 15 year. A 12 year old Scotch is considered an entry level whisky, but we might consider a bourbon or any other American whiskey, that has not been finished in subsequent flavor casks a product of diminishing returns at some point. Maxed out, past its prime. I'm not saying that the Pappys aren't good. They're very good. But my opinion is that the two-thirds of price is about rarity for the oldest expressions and scarcity, whether real or manufactured, for the younger ones. Therefore, learn to discern flavor and quality. Don't just follow the pack or the buzz. Educate your palate and trust your own perceptions. Then you will never become a victim of hype. Disclaimer: If you are unable to take a few sips of alcohol and stop, these postings on To Pair or Not to Pair are probably not for you. If there's a family or personal history of alcoholism or alcohol abuse, or if you take medications or have other health conditions that make alcohol consumption unsafe, these postings are probably not for you. Please check back for postings solely about chocolate. Your readership is much appreciated.

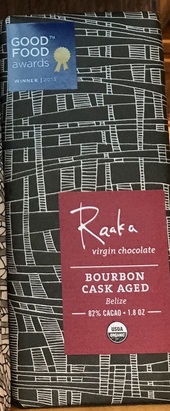

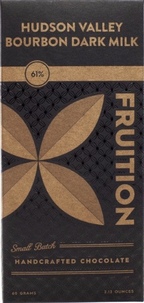

My forthcoming book–The Deep Tasting Guide To Pairing Chocolate and Spirits (Ritual Communications, Spring/Summer 2017) is about savoring, not overindulging in chocolate, and not drinking to the point of intoxication. I will present a way of thinking about matching chocolate with Scotch whisky and other whiskeys, including American bourbon, rye, and craft whiskeys. While I promise to provide many superb matches of fine chocolates and whiskies, or whiskeys, my ultimate goal is to give you the tools to go about discovering good matches for yourself...without going broke in the process. As in the first Deep Tasting Guide™ (Deep Tasting: A Chocolate Lover's Guide to Meditation), the object is to empower you in fine-tuning your ability to perceive and appreciate flavor. In a moment, I'll discuss how to get started finding whiskies, or whiskeys, that may appeal to you. But first, let me define some terms. You may have noticed that I spell "whisky" and "whiskey" two different ways. In Scotland and Canada, "whisky" is the preferred spelling. You may find a preference for that same orthography in Japan and other nations, for historical reasons. In the United States and Ireland "whiskey" has been the customary spelling (with some exceptions). The term "scotch" can only be used legally to describe whisky made in Scotland. The term "bourbon" can only be used legally to describe a whiskey that is made in the United States; it must be at least 51% corn-based and aged in new, charred, oak barrels. If the label says "Kentucky Straight," that means it must be entirely made in Kentucky. A "Tennessee Straight" whiskey means it was made entirely in Tennessee and put through a unique charcoal-filtered process. The term "rye" is not restricted to country of origin, but is assumed to be at least 51% rye-based. The term "expression" is applied to the various products made by the same label; for example, Macallan 12 year, Macallan 18 year, or Jura Superstition, Jura Brooklyn, Johnny Walker Black, Johnny Walker Blue. A whisky is "expressed" through all the complex ways it is crafted, including its ingredients, strength, and the critical aging and finishing processes. Once the whiskey or whisky has been distilled, it must be aged (unless marketed as legal "moonshine" or "white dog.") Aging, typically, takes place for a minimally required number of years, or longer, in American or European or Japanese oak, American ex-bourbon barrels or sherry, rum or cognac casks, or any combination of casks. "Finishing" is a short-term process, often six months, in a cask with residual fortified wine, or other flavorings remaining in the emptied casks. I hinted that whisky can be expensive. For example, if you look at a shelf of fine scotch at a good liquor store, you may find items produced by the same distiller ranging from approximately $60 dollars to, perhaps, $1200 or much more per bottle. We can exclude, for our purposes, the extremely rare, auction-worthy expressions that have gone for tens of thousands, and occasionally into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. (It is worth noting that scotch is appreciating faster than investment-quality wine.) But even the popular-selling, non-investment varieties of scotch can be so theft-worthy that many stores keep the bottles behind locked glass panels. This is true whether we are talking about single malts or blended scotch. And limited or rare editions push up the price still more. In terms of American whiskey, bourbon and rye may start as low as $20, but the higher-end products (longer-aged, "finished," and the craft whiskeys) can go for significantly more. Although they are rapidly appreciating in price, seldom, with rare exceptions, are they as expensive as scotch or Japanese whisky. If you were to go into a liquor store and blindly select a whisk(e)y, only to go home and discover that you didn't like it, that would be a waste of your hard-earned money. So what's a sensible way to go about this process? If you are not an experienced whiskey-drinker (and I wasn't, either!) you will need a roadmap to navigate the thousands of whisk(e)ys in the marketplace today. When I first thought about my new book, I wanted to write about chocolate and "spirits," including rum, which is so compatible with chocolate, and other spirits. But I soon realized that topic is so vast that I had to limit the scope of this second book in the Deep Tasting Guide™ series to just scotch, whisky, whiskey, bourbon, and rye. Then, too, there are thousands of chocolates out there. How do you discover ones that are pleasing to you? How do you find spirits-compatible chocolate? It involves a similar process through understanding and being able to fully experience flavor. (You may find it helpful to read the first book in the Deep Tasting Guide ™ series: Deep Tasting: A Chocolate Lover's Guide to Meditation.) But for now, let's focus on how to begin searching for broad types or "styles" of whisk(e)ys that you may prefer, ones you may wish to enjoy by themselves or match to chocolates later on. And how can you research spirits without needing to take out a second mortgage? Here's a simple and economical way to begin. Start with "airplane" cart- sized, 50ml bottles. They can be found in most liquor stores. These are usually priced under $6. plus tax. (The taxes on alcohol purchases always give me sticker-shock!) Or you can order a "neat" drink (straight up, no ice) at a good local bar, although ordering a drink in a bar will cost you significantly more. While you will find a greater range of labels and expressions in an upscale bar, it's easier to take a 50ml bottle home, unless you're like me and have the audacity to carry a flask into the bar, take a few sips of a fine whisky, and pour the rest into the flask as take-out. But back to the 50ml bottles. You can find a surprising variety types of scotch and whiskey of styles in those tiny bottles, if you're willing to search for them Because blended scotch is about 90% of the market, you will find those mostly readily, rather than single malts. (Although, I have seen some Macallan 12 year recently.) However, blended scotches can be sufficient to give you a hint in the right direction of your taste inclination. Let me say one thing before we go any further: There's no reason to be a single malt scotch snob.What's the difference between a single malt and a blended scotch anyway? A single malt means it is produced by single distillery. The bottled result may come from as little as one single cask and vintage or be "married"(notice, I don't use the word "blended" here to avoid confusion) from barrels of whisky of various ages. The key point is the bottled whisky all comes from the same distiller. A blended scotch, however, means that whiskies may come from several distilleries, be blended, then bottled by the non-distilling company whose name is on the label. Great writers on scotch advise us to respect blends. Master blenders are great artists that create complex and subtle whiskies with harmony and balance, aroma and flavor notes, and textures that can stand up well in a variety of uses, including in cocktails. In fact, blends are becoming trendy again as craft brands. The company Compass Box produces pricey, boutique blends. But let's discuss how you can use the more widely available, popular blends to find your whisky style. I'm going to paint with broad strokes here, because in the last twenty years, aging and finishing has become increasingly complicated. But generally, whether single malts or blends, scotches exhibit aroma and flavor profiles along a continuum, from peaty or smokey to more sherried or fruity. Single malts from the islands off the coast of Scotland; for example, Lagavulan from Islay, tend to be peaty or smokey and pick up notes from the sea, while Speyside or Highland single malts, such as Macallan, tend to reflect their aging in sherry or other types of used fortified wine casks. Blended scotch, from Johnny Walker Black Label to Chivas Regal 12 year, whose master blenders source from dozens of distillieries, also produce scotches on a continuum of smokey to sherried. So if you prefer a Johnny Walker Black Label over a Chivas Regal 12 year, you might prefer a peated whisky. Pick up group of these 50ml bottles of blended scotch, go to the company website or to review sites for more information, and begin to define what your whisky preferences might be. If you prefer the Johnny Walker Black label, then go to your local bar or pub and try various peated whiskies. Similarly, if you prefer the more predominant sherry notes of Chivas, you can try scotches aged in sherry casks. Brand-name bourbon is also easy to obtain in 50ml bottles. Bourbon tends to be sweet due to corn being the dominant ingredient, with vanilla and other notes from those charred American oak barrels. While a bourbon must contain at least 51% corn, any number of grain combinations can make up the remaining 49%. Some, using wheat may be creamier or smoother (for example: Maker's Mark); others, with higher percentages of rye, may be more spicy. Preferring a spicier bourbon may lead you to experiment with rye whiskeys too. Due to the craft distilling movement, bourbons and ryes are becoming sophisticated and more nuanced. Some are now being finished in sherry and other type casks. In fact, there's an ironic, trans-Atlantic twist going on, because distillers of Scotland and Ireland have been using American ex-bourbon barrels for aging for several generations now. The first step, then, is to discover what you like. You may find that what you favor will change over time... or not. Scotch or other whisky. Irish or North American. Some people just like bourbon. Some, rye. There's no right or wrong here. Respect your preferences. Learn to be fully present with your whisk(e)y experiences. Drink moderately and responsibly. Savor... and enjoy! Coming soon!: To Pair or Not to Pair, Part Three Disclaimer: If you are unable to take a few sips of alcohol and stop, these postings on To Pair or Not to Pair are probably not for you. If there's a family or personal history of alcoholism or alcohol abuse, or if you take medications or have other health conditions that make alcohol consumption unsafe, these postings are probably not for you. Please check back for postings solely about chocolate. Your readership is much appreciated. Perhaps, due more to marketing incentives than culinary imperatives, we are seeing more writings and events touting the pairing of chocolate with wine, beer and ale, and spirits. In my book, Deep Tasting: A Chocolate Lover's Guide to Meditation, I stated that I wasn't a wine and chocolate pairing enthusiast. For one thing, wine and foods evolved together over millennia. But not so, wine and chocolate. Cacao has only been known to Europeans for the past 500 years, and as tempered chocolates only since the 19th Century. The ancient Mesoamericans did indeed create fermented beverages with mild alcohol content using cacao bean and pulp, but these had nothing to do with grapes. On a strictly personal level, I confess to a late onset allergy to sulfites. So, no wine for me for the past two decades. But I had a history with wine long before the discovery of the sulfite allergy. And I remember the aroma and flavor of great wines and how they affected my palate. These memories tell me on a visceral level that pairing chocolate wine is a tricky business, often producing more flavor clashes than complementary experiences. There are some people, however, who advertise themselves as chocolate-wine sommeliers. I'm sure they are quite skilled and are able to produce pleasant events based on years of experimentation. Yet, I have often found writings about wine and chocolate confusing. All the more reason to flag down one of these experts. But one thing I have gleaned from articles about wine and chocolate pairing is that it is often more successful with sweeter wines. Hence the ubiquitous truffles containing "champagne" (often just a sweet white wine, sans bubbles, in reality) and various sweet liquor-based centers. In my own kitchen experiments, I've found rum and bourbon to work well in bonbons. I know others use vodka, and I've added a little sake to my spicier recipes. There are ales with added chocolate flavoring. The results tend to be subdued, the chocolate clearly subordinate to the ale. It's easy to understand why brewers might try to add chocolate flavor since there are ales that naturally have chocolate notes. In recent years, some chocolate makers have used bourbon casks to age their chocolate. The first one I recall doing so was Raaka.

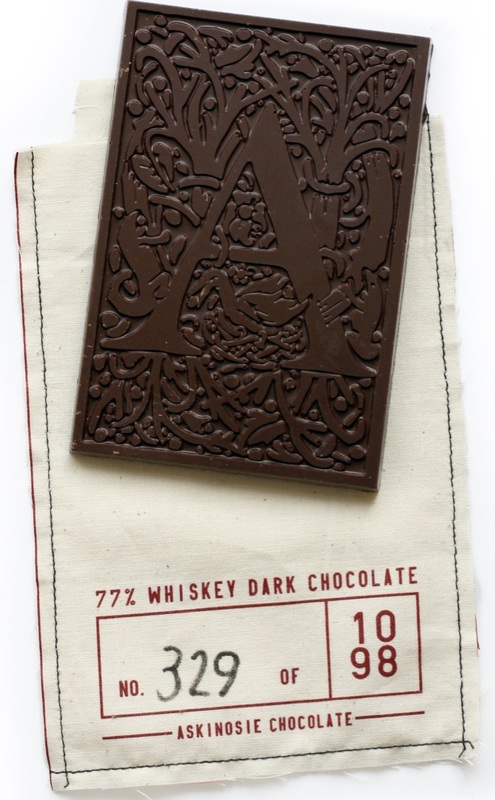

Shawn Askinosie quickly sold out beautiful bars created by aging their Tanzanian nibs for 2 years in Jim Beam casks to create their 1098 line. They only created 1098 commemorative bars on the first go-round. Why 1098? That was the year the Cistercian Order was founded, and Shawn is a family brother at the Assumption Abbey, a Trappist Cistercian monastery. Good news: a new batch of the 1098 bars is expected for Spring 2017. So much for the delightful effects of adding spirits to chocolate, and chocolate to ale and spirits. In these cases, for the most part, either chocolate or the spirits are the main attraction. This is an old fashioned marriage where one is subordinate to the other. In future postings of To Pair or Not To Pair, we'll explore what happens when chocolate and spirits share the stage as modern marriage partners. Will it be a love match made in heaven, or a couple headed for divorce?

Perhaps you're wondering, who is this R. M. Peluso to riff on chocolate? Seems like everyone and her uncle have something to say about chocolate. Credentials? Expertise? Almost dirty words these days. But it's a question I ask, and urge you to ask, of everyone who starts a blog, column or review site on chocolate, and asks you to accept their pronouncements on quality and taste, or tries to influence where you will spend your hard earned chocolate dollars. Usually, my query is met with silence. And the silence speaks loudly.

My riffs will be played assuming basic values of the artisan chocolate community: ethical sourcing, humane working conditions, economic justice, ecosystem preservation and so on. Reviews and commentary begin by informing consumers. It's not about writing ego-gratifying fluff pieces, just because you like chocolate. It isn't about scoring snide take-down points. It isn't about making yourself look clever at the expense of other people's livelihoods. It's about advancing the craft. If no one's learning something, reviewers, commentators and assorted big mouths, haven't done their jobs. These are just gossip columnists with a predilection for chocolate. I promise riffs with more take-away. If I can get you to laugh, that's fine. But it won't be at some little guy's expense. Fair enough! You should ask me. Who am I to riff on chocolate? So, let me introduce myself. I started out training as a taster and reviewer of dark chocolate in 2006 with one of the fussiest noses around--Mark Christian of the C-spot® (C-spot.com). Ten years of experience with Mark as my mentor and the C-spot as my training ground. Even before the C-spot® was launched. And before that, as you'll see in my book, it seemed I was destined to taste. It's been a fascinating journey, and you can read more about it in my newly released book Deep Tasting: A Chocolate Lover's Guide to Meditation. Please visit my author page and check out my book on Amazon.com/author/rmpeluso |

AuthorRev. Dr. R.M. Peluso is an ordained Interfaith minister whose spiritual journey has included meditation and chocolate. She is a writer, chocolate taster/reviewer, a long time contributor to the C-spot.com and, recently, Whisky Magazine (UK), American Whiskey Magazine and Cheese Connoisseur Magazine. Dr. Peluso is the author of Deep Tasting: A Chocolate Lover's Guide to Meditation and Deep Tasting Chocolate & Whiskey. Archives

May 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed